The Smithsonian American Art Museum invited minority artists to illustrate their lives.

Some of this work was exhibited in 2024 and 2025.

Such exhibitions are rare in the US because minority artists have had little funding or sponsorship since the beginning of this country. This is also true of women.

Fire (America) 3, 2016, glazed ceramic

Teresita Fernandez, American born 1968. Whitney Museum of (North) American Art

The murder of the Black American, George Floyd, on a Minnesotan street in May 2020, was followed by a soul searching by cultural institutions and changes in their practices. More and more, the work of minority artists have been showcased and bought for permanent museum collections.

as above

In January 2025, Donald Trump took office.

In March 2025, Trump issued an executive order called “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.” Its goal is to impose an ‘uplifting’ reading of American history.

as above

The Smithsonian, a complex of 19 museums and research institutions, 62% of whose funding is Federal, has been placed under political vetting.

Its remit is to tell the story of the US.

Fire (United States of the Americas), 2017/2020, charcoal.

Teresita Fernandez, American born 1968. Promised gift to the Philadelphia Art Museum.

The charcoal represents scorched earth. Ash drifts into the oceans.

In August 2025, an exhibition at the Smithsonian American Museum was one of several Smithsonian exhibitions characterized as ‘objectionable’ by the Trump administration.

Specifically, the administration objected to the focus on race; and to this unexceptional statement in the exhibition: …race has been used “to establish and maintain systems of power, privilege and disenfranchisement.”

as above

In December 2025, the Trump administration asked the Smithsonian for all wall text from their galleries, all inventories of permanent holdings and all exhibition plans and budgets, including those for programming associated with the country’s 250th anniversary. This falls in 2026.

Further efforts to suborn the Smithsonian in order to control the public narrative of the country’s history and present are continuing.

We are not concerned that artists will cease to work. Or that privately funded institutions will kowtow.

But we are afraid of the fire for which political repression has repeatedly been the tinder in the United States.

**********

Here is work created by minority artists over the last 60 years.

My Arizona, 1943, fiberglass and plexiglass

Isamu Noguchi, 1904-1988 Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

Isamu Noguchi was imprisoned in a detention facility in Arizona during World II. More than 120,000 Japanese were similarly detained. The detention was later recognized as unjust.

Self Portrait at Age 5 with Doll, 1966, oil on canvas with doll.

Adrian Piper, American born 1948. Collection Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation, Berlin.

The artist, from an accomplished and affluent New York family, some of whose members have passed as white, has fought a long battle for equal access to the political, social and economic goods of the country for Black Americans.

Skywatcher, c. 1948, marble

Marion Perkins, 1908-1961, American. Loaned to the Smithsonian American Art Museum by the Illinois State Museum

A remembrance of the dead and injured of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Farm Workers’ Altar, 1967, acrylic on mahogany and plywood

Emmanuel Martinez, American born 1947. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

Cesar Chavez broke a fast of 27 days at this altar in 1968. He had been protesting the conditions of work and wages of Mexican and Filipino migrant workers.

Man on Fire, 1969, fiberglass in acrylic urethane resin on painted wood fiberboard base

Luis Jimenez, 1940-2006. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

A representation of images lingering since childhood and accompanying the artist his life long, of the courage of the Aztec ruler, Cuauhtemoc, whom Spanish invaders burned to death.

Malcolm X #3, 1969, polished bronze, rayon, cotton

Barbara Chase-Riboud, American born 1939. Philadelphia Art Museum

Guarded view, 1991, wood, paint, steel and fabric.

Fred Wilson, American born 1954. MOMA, NY.

The artist points to the fact that, almost the only representation of Black American men in museums are as museum guards (also cleaners, restaurant staff) tasked with safeguarding people and artworks, rarely noticed and often the only people of colour in the galleries. Paid not much.

Acquisitions of art by Black Americans accounted for 2.2%; and 6.3% of exhibitions by them between 2008 and 2020 in an analysis of 350,000 works acquired and nearly 6,000 exhibitions in 31 major North American aft institutions between 2002 and 2021.

15.2% of the population identify as Black or as Black and one or more other race in the 2025 census.

The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972, wood, cotton, plastic, metal, acrylic paint, printed paper and fabric.

Betye Saar, American born 1926. UC Berkley Art Museum on loan to the Smithsonian American Museum, Washington, DC

This well-known image, based on a racist stereotype, dates to a minstrel song of the late 19th century. It was translated into a television series in the middle of the 20th century.

It took until the killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, MN on May 25, 2020 for many people to acknowledge that Aunt Jemima – and other – symbols pertaining to African and native American history are racist.

PepsiCo, the last owner of the image, finally removed Aunt Jemima in June 2020 from its marketing and packaging of Quaker Oats after a widely shared expose on TikTok of Aunt Jemima’s history.

Liberate (25 mammies), 2015, mixed media assemblage.

Betye Saar, American born 1926. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts projects, Los Angeles, CA. Photo: Brian Forrest. Published in ArtNews in June 2020

Broken Dance, Ethnic Heritage Series, 1978-1982. Stainless steel, wood, leather, sewn cloth, ammunition box.

John Outerbridge, 1930-2020, American. MOMA, NY

An evocation using dance of the deformations of a people’s history which are a consequence of slavery and discrimination.

Mexican Chair, 1984, dining chair with acrylic paint and toothpicks (to simulate the spines of cacti)

Yolanda Lopez, 1942-2021, American. Private loan to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2024

The ‘sleeping Mexican’ is a caricature of the lazy, drunken Mexican sleeping against a cactus, an image of whom is painted on the chair’s back.

This image is still used as a marketing tool.

Apache Pull Toy, 1988, painted steel

Bob Haozous, Chiricahua Apache, born 1943, Los Angeles, CA

The white cowboy, made into a toy and thoroughly shot up, is the ‘Indian’ in this reversal of history.

Tears, 1990, deer hide, cow hide, wood, feathers, copper, bone beads, corn, stones, turquoise, and Anasazi pot sherds

Kay Walkingstick, American and Cherokee, born 1935. MOMA, NY

Feather Canoe, 1993, peeled willow, white feathers, and copper wire

Truman Lowe, 1944-2019, Ho-Chunk Nation. Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

A recollection of the Great Lakes canoes of his childhood and the walks with his father to gather the willows used in basketmaking and canoe building.

Rear

Angel: the Shoe Shiner, 1993; painted wood, rubber, fabric, glass, ceramic, shells, painted cast iron, hand-tinted photographs, paper, mirror, two video monitors, and two videos running on each monitor.

Pepon Osorio, Puerto Rican born 1955. Whitney Mueum of American Art, NY

A memorial.

Jerome IV, 2014, oil, gold leaf, and tar on wood panel

Titus Kaphar, American born 1976. The Studio Museum in Harlem. Photo from the web

Searching for the prison records of his estranged father, the artist found 97 mugshots of men with his father’s name. He went on to make devotional sized images on gilded panels of some of these men. This is one.

Black Monolith II, (For Ralph Ellison), 1994; acrylic, black molasses, copper, salt, coal, ash, chocolate, onion, herbs, rust, eggshell, razor blade on canvas.

Jack Whitten, 1939-2018, American. Brooklyn Museum loan to Metropolitan Museum, NY in 2018

The artist memorializes Ralph Ellison (1914-1994) whose Invisible Man of 1952 represented and, to some extent, continues to represent African-American life in the United States.

Julio, Jose, and Junito, 1991/1995, acrylic on plaster

Rigoberto Torres, born 1960, Aguadillo, Puerto Rico. Whitney Museum of Art, NY

Exodus, 2016-17, wood, charcoal, pencil and ink.

Diego H. Rodriguez Carrion, American born Puerto Rico 1995. Woodmere Museum of Art, Philadelphia

This triptych illustrates the desolation of emigration.

Nature overtakes the banana plantations cultivated with care over generations.

Four Hundred Years of Free Labor, 1995, welded found metal.

Joe Minter, American born Birmingham, Alabama, 1943. Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY first collected by the Souls Run Deep Foundation

Last Trumpet, 1995, brass, sousaphone, and trombone bells; four parts

Terry Adkins, 1953-2014, American. MOMA, NY

The artist said he made the horns on the scale at which angels would play them. They were presented first at an exhibition dedicated to his deceased father.

Cihuateotl with Mirror in Private Landscapes and Public Territories, 1997; painted and mirrored armoire, found objects, dried flowers, faux topiaries, family photographs, miniature jeweled trees and painted wooden hedges

Amalia Mesa-Bains, American born 1943. Whitney Museum of American Art

Cihuateotl is an Aztec spirit representing those who have died in childbirth.

She stares at a giant hand mirror which returns her gaze with the image of the Virgin of Montserrat, a Black Madonna popular throughout the Americas. This figure is meant to act as a bridge for women from their earthly terrain to their spiritual guides.

This is one of a series whose subject is the life of Roman Catholic women in meso-America.

1797: Vencedor (1797: Victorious), burlap, fabric, palm tree trunks, wooden seat, steel sheet, boot, talks, bells, rope, plastic bag, baseball glove, coconut, tools, masking tape, shovel, machete, mirror, ribbon, pins, wire.

Daniel Lind-Ramos, Whitney Biennial 2019

Las Twines, 1998, painted plastic life casts, found materials, synthetic fabrics, jewellery, beads, and wood

Pepon Osorio, born Puerto Rico 1955. Smithsonian Museum of American Art

In the background was running on video the story of these twins. Their mother dies and the twins set out to find their father who denies that they are his children.

The story is about colorism: discrimination within an ethnic group against persons of a different shade of ‘black’.

It is a potent psychological and emotional poison because it is practiced within a group of people who are of the same community, family.

Colorism is also practiced between ethnic groups. It is rare to see Black women in the upper echelons of any large institution unless they are fair.

Branded Irons, 2000, scorched plywood panels.

Willie Cole, American born 1955. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia

The mother and grandmother of the artist kept house for others and would often ask him to fix their broken irons.

This work also makes reference to the branding of slaves: a practice which facilitated the return of slaves who escaped.

Five figures made with low fire white clay with oil paint and markers in a series named ‘Isichapuitu’, 1997-2002.

Kukuli Velarde, American born Peru 1962. Woodmere, Philadelphia

The ceramicist represents some aspects of her life.

Tallada

A Mi Muerto

Mi Padre y Yo

The Bride

Yo misma Soy

Frank as Sun King, 2005, mixed media

Syd Carpenter, American born 1953. Promised gift from the artist to Woodmere Museum, Philadelphia

The artist’s brother returned from his service in Desert Storm a quadriplegic. He died of these injuries.

The artist has dipped his army boots in bronze and placed them below this portrait of her brother as Sun King, an image which came to her when she was thinking about him.

Around his head rotate his attributes and those things he loved about his life. The wheel, an old and ordinary and useful creation, is a grounding for her brother’s radiant spirit.

Trail of Tears (Trail of Tears Series and Migrant Series), 2006, oil on four canvases with painted fabric and mixed media collage

Benny Andrews, 1930-2006, American.

Private collection on loan to the Phillips Collection, Washington, DC in 2020

For 20 years after 1830, American Indians were forcibly deported from the south-east of the United States to west of the Mississippi River.

Among these the Cherokee depicted on that march in this work. 1,600 of their African slaves went with them. (There remain Cherokee in western North Carolina descended from resisters).

The number who died on the march is thought to hover around 4000: one quarter of the tribe.

The trail is more than 5000 miles and covers nine states. Less than half has been designated as ‘historic’.

It took until 2008 for the Senate of the United States to render a general apology for ‘past, ill-conceived policies’ towards Indian tribes.

Ancestry/Progeny, 2008, porcelain figures and glass beads

Joyce Scott, American born 1948 Loaned by the artist and her gallery to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2024

The artist critiques the ideal of racial purity and segregation given the miscegenation between races in the US since 1619.

Salish Clam Basket, 2008, blown glass with etched image.

Marvin Oliver, 1946-2019, Quinault/Isleta Pueblo. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

Swing, 2010, car tire with show tips, shoe tongues and rope

Nari Ward, born Jamaica 1983. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

A reference in the shape of a children’s swing to the lynching of Black Americans which continued in the US from the 1830’s to the 1960’s.

Middle Passage, 2011, Claro walnut

David Washington, American born 1955. Woodmere, Philadelphia

Rouse, 2012, wood, bronze, paper, antler sheds, and stamped ceiling tin

Alison Saar, American born 1956. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

This was made when the artist’s daughter went to college.

It is thought to represent the artist, rooted in her history, looking out into a world of new roles which await her energy and focus.

Skywalker/Skyscraper (Axis Mundi), 2012.

Marie Watt, American born 1967. Whitney Museum of American Art.

The artist is a member of the Seneca nation which is part of a confederacy with the Mohawk and four others.

This work is her comment on the large contribution made by Mohawk ironworkers to the building of New York skyscrapers. And the use of blankets of this type at birth and death.

Ohio Gozo y Mas, 2013, blown glass, resin castings, and mixed media

Elnar de la Torre, born 1963 Mexico and Jamex de la Torre, born 1960 Mexico; both active Mexico and the USA. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

The brothers, who are glass artists, based this creation on the Aztec calendar. The title, when spoken seems to be saying ‘Good morning’ in Japanese. Ohio is where this piece was made.

Symbols from different cultures indicate the porous quality of our cultural boundaries:

The Kewpie doll created in the US and widely popularized in Japan; the all-powerful hand from Mexican Catholic devotional imagery; grinning figures from Mesoamerican ceramics; and golden ceremonial knives with semicircular blades, from the ancient Andean Moche culture.

Casts of butterflies and insects symbolize transformation and migration.

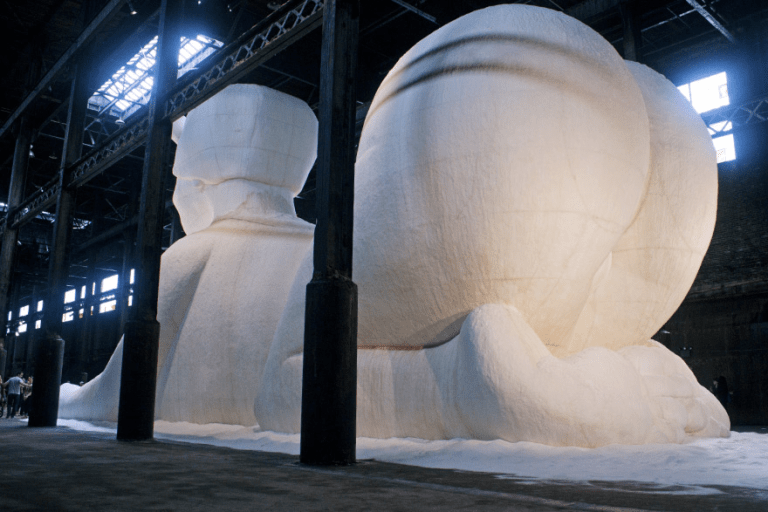

A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby,

an Homage to the Unpaid and Overworked Artisans Who Have Refined Our Sweet Tastes From the Cane Fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the Demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant

2014, polystyrene coated in sugar

Kara Walker, American born 1969. Photo by Jason Wyche © Kara Walker, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., N.Y.; published in the New York Times in June 2019

On display in a Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn, NY which was demolished after this exhibition to be converted (much of it) into condominiums.

A work recalling the history of sugar agriculture: the ‘white gold’ of slavery. The work takes the features of a stereotypical ‘black mammy’ in a kerchief.

Trayvon Martin, Most Precious Blood, 2014, acrylic, matte medium and watercolour paper

Barbara Bullock, American born 1938. Woodmere, Philadelphia from whose website this photo

Trayvon Martin was 17 years old when he was fatally shot by a neighbour watch volunteer in 2012 in a gated community in Florida. Martin was walking home.

His killer was tried and acquitted on the grounds of self-defense even though Martin was simply walking home and offered no interaction of any kind.

The Imaginary Indian Totem Pole, 2016, wood, acrylic paint and floral wallpaper

Nicholas Galanin, Lingit/Unangax, born 1979, Sitka, AK

This is a design from the Pacific Northwest. It was, however, carved in Indonesia for the tourist trade in Alaska.

Dream Machine, 2016, ceramic, steel, leather and rope

Rose B. Simpson, Kha’p’oe Owingeh (Santa Clara Pueblo), born 1963, New Mexico. Smithsonian American Art Museum

The artist has an interest in post-apocalyptic futures. The helicopter may refer to this. Or, it may refer to the endless invasions of other nations by the US.

New American Landscapes. Self-Portrait: Catching Feelings (Ecstatic), 2017. Wood, bailing wire, adobe, scorched twigs, condom wrappers, glass shard, synthetic and agave fiber rope, dry roots and acrylic paint.

rafa esparza, American born 1981. Whitney Museum of (North) American Art, NY

Octoroon, 2018, canvas and thread

Sonya Clark, American. Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA loan to the American Smithsonian American Art Museum

An American flag made into a reminder of the notion that one drop of ‘African’ blood made a person ‘Black’ into the 20th century in some parts of the US. An octoroon was one-eighth Black.

Ta Saparot (Pineapple Eyes) glazed ceramic with found shards, glitter and gold

Linda Sormin, no DOB, born Thailand active US

The artist represents the chaos and constant threat of the unravelling of a life which migration brings.

She migrated with her family first to Canada and then to the US for art school.

When will the Red Leader Overshadow Images of the 19th Century Noble Savage in Hollywood Films that Some Think are Sympathetic to American Indians,

2018, 35mm film from “Windwalker” (1981), red and white film leader, silver braid

Gail Tremblay, 1945-2023, American. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

This basket mocks the stereotypes of American Indians in so many American films.

It incorporates 35mm film from the 1981 western Windwalker, in which one Native American tribe is portrayed as noble and the other as villainous.

The red film and the reference to “Red Leader” in the basket’s title symbolize the derogatory term used to describe Native Americans. The artist twists the film into a prickly porcupine stitch.

Lady Interbellum, marble on cedar plinth, 2020

Sanford Biggers, American born 1970. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

The artist asks why African sculpture is not considered as museum-worthy as classical European sculpture.

Village Series, 2020, stoneware

Simone Leigh, American born 1968. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

Initiate, 2020, ceramic

Donté Hayes, American born 1975. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

The artist used a needle to simulate the skin of the pineapple.

The pineapple, introduced to Europe by Christopher Columbus and long a symbol of hospitality and luxe, is also a symbol of the the brutality of the Caribbean and South American fruit plantations where it was cultivated.

Tiger Banana, 2023, stoneware with underglaze, glaze and synthetic hair

Jhia Moon, born 1973 Daegu, South Korea. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

Tiger and banana are two racist slurs used for Asian Americans in the US.

Do You Speak Indian? 2018, glazed stoneware

Raven Halfmoon, Caddo Nation, born 1991, Norman, Oklahama. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

The artist calls out the widespread ignorance of American Indian history and culture.

Pueblo Revolt 2180, 2018-19, white bentonite clay with bee-weed (spinach) paint

Virgil Ortiz born 1969 Puerto Rico. Smithsonian American Art Museum

The title refers to the 1680s revolts when Pueblos overthrew Spanish invaders. The title makes reference to the unstable relationship of Puerto Rico and the US.

Carry III, 2020; buckram, synthetic sinew and thread, vintage glass beads, brass sequins, copper vessel, copper ladle.

Dyani White Hawk, Sicangu Lakota born 1976 Madison, WI. On loan from the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MI to the Baltimore Museum in 2024

It is water that is being carried.

Arm Peace, 2019, bronze and found metal objects

Nick Cave, American born 1959. Loaned by the artist to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, NY in 2022

This is a cast of the artist’s arm in a gesture of peace.

Hygeia, 2020, mixed media installation Alison Saar, 2020, American born 1956.

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia

DNA Study Revisited, 2022, urethane resin life cast, foam, wire, acrylic paint

Roberto Lugo, American born 1981. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

The artist painted a resin cast of his own body. Each of the 4 patterns represents his ancestors: from head to toe: Taino (Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean), Spanish, African and Portuguese.

Three of Four creations installed in the porticoes at the front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY 2025/26 (The Genesis Facade Commission)

“they carry messages between light and dark spaces biakak / dawodv / hawk”

“The Animal Therefore I Am,” 2025. Silicon bronze with patina finish.

Jeffrey Gibson, American Mississipi Choctaw/Cherokee born 1972. Courtesy the artist. Image credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Photo by Eugenia Burnett Tinsley.

“they plan and prepare for the future fvni / sa lo li/squirrel”

“The Animal Therefore I Am,” 2025. Silicon bronze with patina finish.

Jeffrey Gibson, American Mississipi Choctaw/Cherokee born 1972. Courtesy the artist. Image credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Photo by Eugenia Burnett Tinsley.

“they teach us to be sensitive and to trust our instincts issi / awi / deer”

“The Animal Therefore I Am,” 2025. Silicon bronze with patina finish.

Jeffrey Gibson, American Mississipi Choctaw/Cherokee born 1972. Courtesy the artist. Image credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Photo by Eugenia Burnett Tinsley.

The artist took his inspiration from a work of Jacques Derrida, ‘The Animal That Therefore I Am’ (lectures published in book form in 2006). Derrida critiques the idea of human primacy over all animals.

Gibson lives in the Hudson Valley. Collecting driftwood near his home, he bundled the wood into animal forms. He used wax, wood, taxidermied pelts and hide to create each form. They were then digitally scanned and cast in bronze. Each is 10″ tall.

The question being asked is what kind of relationship ought we to have with non-human animals, here presented in upright, human pose and ready for dialogue.

<3

As always, your post fascinated me.

The artworks and their details are truly amazing!

Thanks for your comment, Luisa! Glad you found it interesting….

It was my pleasure, dear Sarah