We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Preamble to the Constitution of the United States, created 1787, Philadelphia, in force June 1789

.

This famous preamble does not, of course, have the force of law. It assigns no powers to any institution. It stands as an ideal.

It carries the moral charge of North American civilization; and it is still discharging because its promise has not yet been fulfilled.

Woodmere Museum of the Arts of Philadelphia and its Region has taken up the charge in a remarkable exhibition which showcases one of the main functions of museums: the exposition, by way of art, of the critical questions of the day, no matter how difficult those questions are.

Woodmere’s focus in this expose is on the changing representation of intimate relationships from Colonial times until now given the history of unequal power between races, genders, sexual orientations, religious traditions.

A Colonial Wedding, c. 1888, oil on canvas. Frederick James, 1845-1907, oil on canvas

Where, Woodmere is asking, are we?

Why do the contemporary artists in this exhibition unanimously agree that the subject matter of this exhibition is very important at this time in the United States?

What is this all about?

Justice and Liberty and the General Welfare

This world is, of course, three worlds for all of us.

One is our physical world: our physical bodies in the physical world.

The second the cultural, political, and economic world in which we live and to which we are expected to conform. Then, of course, our third world: the spiritual.

The Song of the Reed, 2006-16, acrylic. Kassem Amoudi, American born Jordan, 1951.

Of the three, it is the physical world which is the essential precondition of our lives.

A common and garden truth which the evolution of our consciousness, the supremacy of our species with its immense ego and imagination, the extreme rationality of our Western intellectual tradition with its addiction to ideas, have obfuscated.

Not to speak of some of our major religions which want to assuage our fear of dying by pointing to other worlds in which we will live.

No body, no life. To our rational knowledge, only one life here on earth.

It follows that, first and foremost, we need to reconcile our flesh to the physical world as it is. Not submit our flesh, but reconcile it: struggles are involved.

The world is not made in any of our images and the reconciliation – again, I am not talking about submission – of the flesh to the world is the essential precondition of a realized life and of a mature society.

Without this effort, no expanding liberty, no expanding justice or welfare. And all three are the promise of our Western civilization.

We ride on and have our roots and anchor in, take our entire sustenance from, and derive the energy, shape, intensity, beauty, efficacity, sorrow, difficulty, force and joy of our lives from the reconciliation of our flesh to the physical world.

This project of reconciliation is our spiritual life; and our spiritual life does not exist except in our physical interactions with other people and in our behavior towards all things living.

We can see all around how far we have yet to go. This is the urgency to which the contemporary artists in this exhibition are pointing.

The Song of the Reed, detail, 2006-16, acrylic. Kassem Amoudi, American born Jordan, 1951.

The reed, the artist says, is the reed cut, according to the story by the Sufi mystic, Jalal al-Din Rumi (1207-1273) from a bed of reeds to make a flute whose plaintive sound is an expression of its sadness at separation from the native ground of its being.

We, says Rumi, are those reeds.

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, says Rumi

there is a field. I’ll meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass,

the world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the phrase ‘each other’ doesn’t make any sense.

Translation by Coleman Barks, American poet, born 1937.

This painting is not, in the first instance, about physical intimacy or love. It is pointing to the spiritual function of the work of reconciling our flesh to the world, to other people, to the earth. Human love, for this mystic, as for all others, is a reflection of human need for identification with the source of the life of our world. The practice of love for anything or anyone is one of the main ways in which we reconcile our flesh to the world.

That it is irregular to hear discussion of this does not mean that this is not true. It means only that we are seculars and don’t habitually use this language.

One of the primary areas in which we struggle with this reconciliation is in our intimate lives.

It goes without saying that all human experience tracks through the body and leaves there its marks, its consequences, for good or ill.

What Woodmere is showing is just this: our energy, our shapes, our intensity, beauty, efficacy, sorrow, difficulty, joy and force in the area of our intimate relationships.

That is, in the reconciliation of our flesh to the world as it is in its diversity.

In the absence of our continuous efforts to reconcile ourselves, we will regress.

We are afraid that our civilization, which has well-known original sins because whole categories of people were excluded from the Constitution of 1787, has begun regressing.

This is a remarkable exhibition, conceived both with intelligence and passion. And timely.

For which I thank the artist, Frank Bramblett, 1947 – 2015, and the director of The Woodmere, Bill Valerio.

***********************************

A More Perfect Union?

Power, Sex and Race in the Representation of Couples

Woodmere Museum, Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia. Until May 21, 2017

Hotel, and detail, 2008. Alex Kanevsky, American born Russia 1963

The Happiest Day of Our Lives, 2008, acrylic on Mylar on panel. Peter Paone, American, born 1936

Lindsay Vandermay (right) and Ashley Wilson (now Lindsay and Ashely Wilson) were the first same-sex couple to marry in Philadelphia. Digital print by Joseph Kaczmarek, May 23, 2014

Dance, Brenda and Helmut Gottschild, 2007, earth, pigment, and casein on 100% rag paper, diptych. Donald E. Camp, American born 1940

Two Men on a Bed, 2015, acrylic on panel. Jonathan Chase, American, born 1989

Loving Embrace, and detail, 1985, graphite on paper. Ellen Powell Tiberino, 1938-1992, American. The artist was fatally ill when she drew this self-portrait with her husband

Dark Gods, and detail, 1982, acrylic on canvas. Barbara Bullock, American born 1938

Hypothetical Marriage of Monsieur Marcel Duchamp and Miss Helen Keller, 1982; floor tile, silicon rubber, mirror, glass, enamel, chalk and felt on panel. Frank Bramblett, 1947-2015. Woodmere Museum, Philadelphia.

The director of Woodmere notes that it was in discussing this work with the artist that the idea for this exhibition emerged.

In this work, the artist comments on several aspects of his life: his loving relationship with his wife; his own belonging to both Alabama and Pennsylvania (he was born and raised in Alabama, Helen Keller’s native state. He lived the greater part of his creative life in Philadelphia.

The artist is also commenting on the presence in the city of the major work of our iconoclastic master, Marcel Duchamp, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

*********************************

A comment from Marcel Duchamp’s work.

In this, The Large Glass, along with his Fountain of a urinal, probably the artist’s most famous pieces, and in the secret work found after his death, also at the Philadelphia Museum, Marcel Duchamp speaks to the difficulties and dangers of the reconciliation of the flesh.

The top half of the glass is the Bride’s Domain; and is a view of what surrounds the bride from the Milky Way all the way to her garment and mechanical and mystical elements operating on her environment.

The lower half belongs to the Bachelors – the Bachelor Apparatus – men (Duchamp gives the Bride the pick of a priest, a delivery boy, a gendarme, a cavalryman, a policeman, an undertaker, a liveried servant, a busboy and a stationmaster) and various artifacts – all with meanings in the artist’s private lexicon – whose intended uses are for the capture of the bride.

Marcel Duchamp said that this work, in which the bride escapes the attention of her suitors, is about constant sexual frustration.

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-1923, oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, and dust on two glass panels. Marcel Duchamp, 1887-1968, American born France. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Subsequently, Duchamp more than made this woman his bride.

He cut her head off.

Then he had his secret way with her headless body for years until he died.

In a cork-floored, step-muffling alcove near The Large Glass at the Philadelphia Museum is a small room with a ceiling-to-floor locked wooden door.

Through a small peephole can be seen a headless, nude female torso, her genitalia exposed to full view and all of her lit by a gas lamp which she is holding high. Only one person to look at a time. Its misleading title is Etant donnes 1° la chute d’eau 2° le gaz d’éclairage, (“Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas”). 1946-1966.

**********************************

Womb of Creation, and detail, 1951, oil on canvas. William Newport Goodell, 1908-1999, American.

Country Lovers, from the series Eroticard, 1975, ink on paper. Roland Ayers, 1932-2014

Triad, 2012, archival pigment print. Sebastian Collett, American born 1973

Bedroom 2, intaglio print, 1985. Sarah McEneaney, American born Germany, 1955

Two gelatin silver prints, 1983-85, from the book Vents from Behance. Laurence Saltzmann, American born 1944

The Tarantula Nebula, 2003, oil on canvas. Martha Mayer Erlebacher, 1937-2013, American

View Finder, c. 1989, oil on canvas. Bo Bartlett, American born 1985

American Holocaust 6 and 7, graphite on paper, 2006-2008. Charles Kaprelian, American, born 1938. The artist was addressing the illness and death of his wife, Inge

Fortune Teller and Harlequin, date unknown, gouache on board. Roger Anliker, 1924-2013, American

A View From the Box, 2016, plaster model cast. Christopher Smith, American, born 1958

Eighty Percent Match, 2016, acrylic on panel. Sterling Shaw, American born 1982

The Path, oil on canvas, 1999. Martha Mayer Erlebacher, 1937-2013, American

Made From Kodak Negatives, and detail, 2016, inkjet prints. Kaytleen Dunphy, American, born 1993

Self-portrait with Albert, 1969, oil on linen. Edith Neff, 1943-1995, American

Parts and Counterparts: Embrace, 1969, collotype. Samuel Maitin, 1928-2004, American

Untitled (Woman with Artist), and details, c. 1980’s, oil on canvas. Ben Kamihira, 1924-2004, American

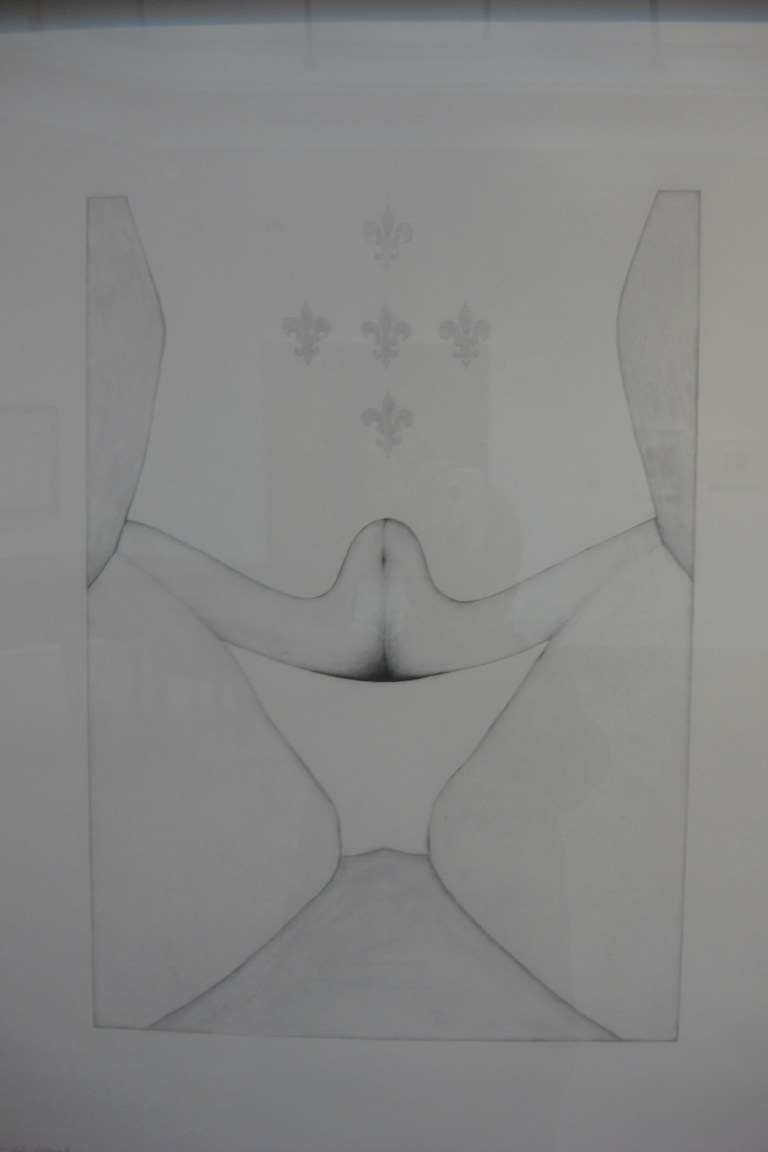

Bridal Vestment I and II, 2006, graphite on rag paper, diptych. Ann Minich, American, born 1934

Adam and Eve, 1958, oil on canvas. Jessie Drew-Bear, 1879-1962, American born England

Prince Charming and Sleeping Beauty from the series, A Mythic History, 1977, lead alloy. Walter Ellerbacher, 1933-1991, American, born Germany

Adam and Eve, 2010, acrylic on panel. Peter Paone, American born 1936

Immortal Beloved, date unknown, pastel and charcoal on paper. Jacob Landau, American, 1917-2001. The artist’s wife died of early onset Alzheimer’s disease

Morning Ritual, 2016, mixed media on canvas. Mickayel Thurin, American, born 1987

****************************