Contrapposto

Bruce Nauman, American born 1941

Philadelphia Art Musuem, Autumn through Spring, 2016-2017

1968

The American artist, Bruce Nauman, says the museum, began in 1968, not long after he came out of art school, to think about the appearance in classical Greek sculpture of the sway of the hips (contrapposto). We cannot move without this sway. He photographed himself traversing a narrow corridor, which he had built, while practicing contrapposto.

I smiled to see this: I remembered how heavily socialized I was in my Puritan youth not to sway my hips in this way. And how, of course, models on catwalks are trained to suppress that sway by placing one foot directly in front of the other – noon we called this gait when children, when walking. Impermissibly sexy. Ostentatiously vulgar.

Bruce Nauman said that he began first to focus on himself as a professional artist because he did not have money for materials.

Then he moved on to think about the artist, the object and his studio. Then, as we know, he moved on to think about politics, ethics, the relationship of words to actions. Often with humour. And recently about alienation and despair.

2015/2016

In 2015/2016, the artist reprised the practice of contrapposto in seven large-scale video projections, in negative and positive, and moving forwards and turning round, moving back. He was 74 in 2015 and is very famous for his pioneering audiovisual and multi-media work using neon, holograms, videotape and performance, and for his sculptures and prints.

In 2015/2016, the swing of the hip is not pronounced and is no more than occurs when one is walking. The artist keeps his arms up, straight up, as in 1967, above his head and has to bring them down periodically for a rest.

The only sound which accompanies both works is the sound of the artist’s shoes in contact with the floor.

There is rarely anyone in these rooms with Bruce Nauman’s video. Some walk through barely turning their heads. There would, of course, be everyone in these rooms if the sound track had not been of the artist’s footsteps but of music: something with a beat.

I decided to stay some time.

What is this all about, I thought?

Perhaps, I thought, this is not something that the artist wants me to grasp with my mind. After all, this artist is famous for his irony and his greater interest in process than in product.

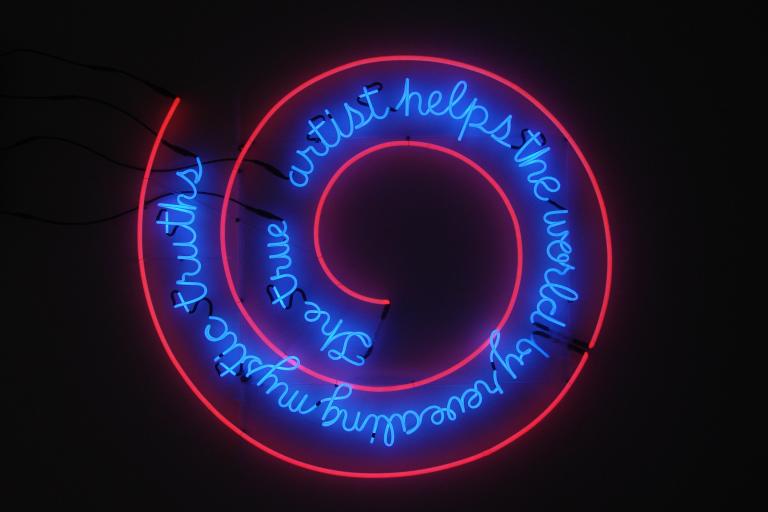

The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths, 1967, neon, clear glass tubing suspension supports. Bruce Nauman, born 1941, American. Philadelphia Art Museum

On the other hand, this artist is also known for preferring meaning to aesthetics.

So I sat while the artist walked.

Sat still and took in the sounds through my ears. And the artist’s physical presence moved with sudden breakages and reversals in and out of my eyes. Black and white and soft grays.

This is not a walking meditation. There is too much attention to and tension in the raised arms for this action to be meditative.

Certainly this is about the passage of time, a not uncommon subject for this artist.

The phrase I hear most often is: I have to go now. We rush from activity to activity even if the only activity is to peruse the net. We have schedules, either real or in our heads. We treat time as though it has to be carefully parsed and often we allot time to people by virtue of what those people can effect for us.

The artist here is operating in a contrary manner. He is marking the passage of time with concentration. He is not rushing away anywhere. And he is not pretending that his time is precious and his activity important, to be withdrawn from our gaze to some place where we do not exist.

Certainly this is about the artist reprising his journey at 27. So the question is: what for this artist was the original journey about?

At 27 the artist was not known and had very limited resources. The narrow corridor he created was a metaphor for his world.

That narrow space has expanded into the world. The artist has not said this but it would not surprise me if he were to say that all his art came from that original journey in which he tested the limits of a classical Greek breakthrough: the representation of the human body in its recognizably human form in our world. The Greek artist’s reconciliation – not submission – of the human body as it is to the world.

This world is, of course, three worlds for all of us.

One is our physical world: our physical bodies in our world.

The second the cultural, political, and economic world in which we live and to which we are expected to conform. There is, of course, our third world: the spiritual.

Of the three, it is the physical world which is first and foremost, the essential precondition.

A common and garden truth which the evolution of our consciousness, the supremacy of our species with its immense imagination, the extreme rationality of our Western intellectual tradition with its addiction to ideas, have obfuscated. Not to speak of some of our major religions which want to assuage our fear of dying by pointing to other worlds in which we will live.

No body, no life. Only one life here on earth.

At 27 Bruce Nauman made visual the reconciliation – not the submission – of his flesh to the physical world. A passage through a narrow corridor, touching each side with his body. His body taking a position and then its counter-position experienced against the limits of the world.

It is, of course, in the second of these worlds – our socio-cultural world and the world of our ideas – that the artist has achieved his enormous success. His subsequent work attests to his exploration of positions which are, in the main, counter to the accepted wisdom or unconventional because hidden from normal view.

At 74, here he is again walking. The corridor is not there. The artist is in the world. We are invited to experience this with him.

Almost a half century later, with a huge and influential body of work behind him, the artist is again making visual the reconciliation – not the submission, I repeat – of his body to the physical world.

That he is older is obvious now. His gait is different. His face has aged. The sway of his hips is diminished. Even his T-shirt – little holes in them – is older than the pristine one he wore in 1967.

The artist’s movements are poised, regular, sure, unhurried, without any hint of self-satisfaction or discomfort and with no triumphalism of any kind. Just as is. What anyone has to say about this effort, as of the effort almost 50 years earlier, is of no concern to him.

A man not unaware of what his life work has achieved. After all, an important museum has filled three rooms with the sound and sight of his walking. And a massive retrospective is promised us by MOMA in 2018.

A man marking the passing of time, the reconciliation – not the submission – of his changed physical self to a changed world with no mention in this performance of his immense achievement in our international culture.

This is instructive to all of us millions struggling to accommodate our actual physical selves to the world. Nor would it be correct to say that Bruce Nauman had it easier on this journey than the rest of us because he is a white male.

The world is not made in any of our images and the reconciliation – again, I am not talking about submission- of the flesh to the world is the essential precondition of a realized life. The essential precondition without which we will not reach contentment. We will accomplish very little.

All our lives we need to focus on this endless reconciliation. It is our most important work.

It entails the guarding of our mental and physical health, our relationship with other people, with our work, with our communities, with other species, with the earth. These ride on and have their anchor in and derive their energy, shape, intensity, beauty, efficacity and force from the reconciliation of our bodies to the physical world.

This entire project is our spiritual life which does not exist except in our physical actions outside ourselves and in the world.

This is what Bruce Nauman told me.

And it is no wonder that Robert Motherwell‘s magnificent 1978 painting on this subject in the East Wing of the National Gallery in Washington, DC is called Reconciliation Elegy. Because this is hard and the probability that we will fail is equal to the probability that we will succeed.

I passed the word on to a young woman. Go there, sit still and turn off all your I’s, I told her: it will help you resist the excesses and it will comfort you, I said, even if you cannot define in words how he helped you until you are older.

I will, she said. I will go right away to be with him. Stay with him awhile, I said. Don’t be rushing out of the room. Promise, I said. I promise, she said. I have to go now, she said………..

The gospel according to Bruce Nauman below in one of his most famous pieces: the many ways of being, living and dying in the flesh

One Hundred Live and Die, Bruce Nauman, 1984, Benesse House Museum, Naoshima Island, Japan

.